- Home

- Henrik Ibsen

Six Plays

Six Plays Read online

Table of Contents

FROM THE PAGES OF SIX PLAYS BY HENRIK IBSEN

Title Page

Copyright Page

HENRIK IBSEN

The World of HENRIK IBSEN

Introduction

PEER GYNT (1867)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

SCENE FIRST

SCENE SECOND

SCENE THIRD

ACT SECOND

SCENE FIRST

SCENE SECOND

SCENE THIRD

SCENE FOURTH

SCENE FIFTH

SCENE SIXTH

SCENE SEVENTH

SCENE EIGHTH

ACT THIRD

SCENE FIRST

SCENE SECOND

SCENE THIRD

SCENE FOURTH

ACT FOURTH

SCENE FIRST

SCENE SECOND

SCENE THIRD

SCENE FOURTH

SCENE FIFTH

SCENE SIXTH

SCENE SEVENTH

SCENE EIGHTH

SCENE NINTH

SCENE TENTH

SCENE ELEVENTH

SCENE TWELFTH

SCENE THIRTEENTH

ACT FIFTH

SCENE FIRST

SCENE SECOND

SCENE THIRD

SCENE FOURTH

SCENE FIFTH

SCENE SIXTH

SCENE SEVENTH

SCENE EIGHTH

SCENE NINTH

SCENE TENTH

A DOLL’S HOUSE (1879)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

ACT SECOND

ACT THIRD

GHOSTS: A FAMILY DRAMA IN THREE ACTS (1881)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

ACT SECOND

ACT THIRD

THE WILD DUCK (1884)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

ACT SECOND

ACT THIRD

ACT FOURTH

ACT FIFTH

HEDDA GABLER (1890)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

ACT SECOND

ACT THIRD

ACT FOURTH

THE MASTER BUILDER (1892)

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERS

ACT FIRST

ACT SECOND

ACT THIRD

INSPIRED BY HENRIK IBSEN

COMMENTS & QUESTIONS

FOR FURTHER READING

FROM THE PAGES OF SIX PLAYS BY HENRIK IBSEN

Home life ceases to be free and beautiful as soon as it is founded on borrowing and debt. (from A Doll’s House, page 217)

Our house has been nothing but a play-room. Here I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I used to be papa’s doll-child. And the children, in their turn, have been my dolls. I thought it fun when you played with me, just as the children did when I played with them. That has been our marriage, Torvald. (from A Doll’s House, page 313)

I believe that before all else I am a human being, just as much as you are—or at least that I should try to become one. (from A Doll’s House, page 315)

It is the very mark of the spirit of rebellion to crave for happiness in this life. What right have we human beings to happiness? (from Ghosts, page 356)

I almost think we are all of us ghosts, Pastor Manders. It is not only what we have inherited from our father and mother that “walks” in us. It is all sorts of dead ideas, and lifeless old beliefs, and so forth. They have no vitality, but they cling to us all the same, and we cannot shake them off. Whenever I take up a newspaper, I seem to see ghosts gliding between the lines. There must be ghosts all the country over, as thick as the sands of the sea. And then we are, one and all, so pitifully afraid of the light. (from Ghosts, page 372)

I always think there’s no harm in being a bit civil to folks that have seen better days. (from The Wild Duck, page 429)

Always do that, wild ducks do. They shoot to the bottom as deep as they can get, sir—and bite themselves fast in the tangle and seaweed—and all the devil’s own mess that grows down there. And they never come up again. (from The Wild Duck, page 476)

I think he regards me simply as a useful property. And then it doesn’t cost much to keep me. I am not expensive. (from Hedda Gabler, page 604)

Tell me now, Hedda—was there not love at the bottom of our friendship? On your side, did you not feel as though you might purge my stains away—if I made you my confessor? Was it not so? (from Hedda Gabler, page 643)

One is not always mistress of one’s thoughts. (from Hedda Gabler, page 681)

I will never retire! I will never give way to anybody! Never of my own free will. Never in this world will I do that! (from The Master Builder, page 716)

I must tell you—I have begun to be so afraid—so terribly afraid of the younger generation. (from The Master Builder, page 751)

It is the small losses in life that cut one to the heart—the loss of all that other people look upon as almost nothing. (from The Master Builder, pages 798-799)

The present texts are from the Charles Scribner’s Sons edition of The Works of Henrik

Ibsen, edited by William Archer and published in 1911.

Introduction, Notes, and For Further Reading Copyright © 2003 by Martin Puchner.

Note on Henrik Ibsen, The World of Henrik Ibsen, Inspired by Henrik Ibsen,

and Comments & Questions Copyright © 2003 by Fine Creative Media, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Barnes & Noble Classics and the Barnes & Noble Classics colophon are

trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Six Plays by Henrik Ibsen

ISBN 1-59308-061-1

eISBN : 978-1-411-43168-3

LC Control Number 2003108032

Produced by:

Fine Creative Media, Inc.

322 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10001

President & Publisher: Michael J. Fine

Consulting Editorial Director: George Stade

Editor: Jeffrey Broesche

Editorial Research: Jason Baker

Vice-President Production: Stan Last

Senior Production Manager: Mark A. Jordan

Production Editor: Kerriebeth Mello

Printed in the United States of America

QM

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FIRST PRINTING

HENRIK IBSEN

HENRIK JOHAN IBSEN WAS born on March 20, 1828, in a small Norwegian town. After his father, a merchant, lost his business, the family lived in poverty. In 1844 Henrik took his first job as an apothecary’s apprentice. In 1850, hoping for a career in medicine, he moved to Christiania (present-day Oslo) to attend a preparatory school; to support himself, he wrote plays and edited a weekly journal of satire. That same year he published his first play, Catiline, under a pen name.

After failing the university entrance exams, Ibsen took a job as a stage director and playwright at the Norwegian Theater in Bergen, where he wrote plays based on history and folklore. In 1857 he joined the Norwegian Theater in Christiania as artistic director; by the time the theater went bankrupt in 1862, he had come into his own as a writer. With financial help from government and private sources, he left Norway to spend the next twenty-seven years living abroad, mainly in Italy and Germany. Ibsen’s early period culminated in the poetic dramas Brand (1866) and Peer Gynt (1867).

By 1870 Ibsen was in his second creative period, writing plays that implicitly criticized the social realities of the day. Among his greatest works of this period are A Doll’s House (1879), Ghosts (1881), The Wild Duck (1884), and Hedda Gabler (1890). Ibsen was especially good at portraying female characters. Both Nora Helmer of A Doll’s House and the title character of Hedda Gabler have intrigued and outraged theatergoers and readers since the plays first appeared. Ghosts, with its attack on social conventions and obligations, and TheWild Duck, which explores the values and risks inherent in idealism, were likewise praised and denounced. Despite the criticism leveled at Ibsen’s work, throughout the last decades of the century it gained widespread recognition and acclaim. Many of the plays Ibsen wrote in the last years of his life—including The Master Builder (1892), Little Eyolf (1894), and When We Dead Awaken (1899)—were highly symbolic. John Gabriel Borkman (1896) continued the social realism of his earlier writing.

Ibsen was the founder of modern prose drama. In discarding old-fashioned plots and emphasizing instead the psychological and moral depths of his characters and their profound conflicts with society and its conventions, he revolutionized dramatic writing. One of our greatest playwrights, Henrik Ibsen died in Christiania on May 23, 1906.

The World of HENRIK IBSEN

1828 Henrik Johan Ibsen is born on March 20 in Skien, a small town in southern Norway.

1835 Henrik’s father is forced to abandon his business.

1844 Henrik becomes an apothecary’s apprentice in Grimstad, a coastal hamlet 70 miles south of Skien. He studies at night for the university entrance exams and begins writing his first play, Catiline.

1849 Ibsen completes Catiline.

1850 He moves to Christiania (

present-day Oslo) to attend the Heltberg School, which prepares students for university study. He edits Andhrimner, a satirical weekly journal, to cover his ex penses, and befriends Norwegian writer Bjørnsterne Bjørn son. Ibsen publishes Catiline under the pseudonym Brynjolf Bjarme. His one-act play The Warrior’s Barrow premieres at the Christiania Theater.

1851 After failing the university entrance exams, Ibsen is hired as stage director and playwright at the Norwegian Theater in Bergen; he is to create a new play each year. In his first creative period, he writes poetic dramas with themes relating to his tory and folklore, but his early plays are not well received. He studies the works of the French writer Augustine-Eugène Scribe, whose formula for the “well-made play” he would later reject. He reads Hermann Hettner’s Das moderne Drama, a trea tise for a new theater.

1853 St. John’s Night premieres in Bergen.

1854 A revised rendition of The Warrior’s Barrow premieres in Bergen.

1855 Lady Inger of Østraat, about the liberation of medieval Norway, premieres in Bergen.

1856 The Feast at Solhaug premieres in Bergen. Ibsen becomes en gaged to Suzannah Thoresen.

1857 Ibsen is hired as artistic director of the Norwegian Theater in Christiania. The play Olaf Liljekrans opens.

1858 The Vikings at Helgeland, a historical drama, opens. Ibsen mar ries Suzannah Thoresen.

1859 Ibsen writes the poems “On the Heights” and “In the Gallery.” His son, Sigurd, is born.

1860 Ibsen writes Svanhild, a draft of the later Love’s Comedy.

1862 The Norwegian Theater in Christiania goes bankrupt. Ibsen receives a grant to collect folklore. He establishes himself as a writer with publication of Love’s Comedy, a satire on marriage. He becomes a consultant at the Norwegian Theater at Chris tiania.

1863 The play The Pretenders, set in medieval Norway, and the poem “A Brother in Need” are published.

1864 The Pretenders premieres. With the support of a grant, Ibsen goes to Rome, where he will live for the next four years; he will live abroad until 1891, doing most of his writing in Italy and Germany, and returning to Norway only for short visits in 1874 and 1885.

1866 He achieves prominence with publication of Brand, a drama in rhyming couplets about a minister whose extreme religiosity strips him of human sympathy and warmth; it is a huge success in Norway. He is awarded a Norwegian government stipend for artists.

1867 Peer Gynt, another poetic drama, premieres; the title character is a self-centered yet lovable opportunist.

1868 Ibsen and his family move to Dresden, Germany, where they will live for the next seven years.

1869 Ibsen begins the second stage of his career, in which he writes realistic social plays and expands the setting of his plays beyond Norway. The League of Youth, a political satire, premieres.

1871 He publishes Poems, his only collection of verse.

1873 He completes Emperor and Galilean, a drama about the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate.

1874 Ibsen commissions Edvard Grieg to write the incidental music for a staging of Peer Gynt.

1875 Ibsen relocates to Munich, where he will live for three years.

1876 The production of Peer Gynt set to music by Grieg premieres.

1877 Pillars of Society, a satire on small-town politics, premieres in Copenhagen.

1878 Ibsen moves back to Rome, where for the next seven years he spends a majority of his time.

1879 Ibsen completes A Doll’s House, a social drama about marriage. It premieres in Copenhagen, applauded by many theatergoers but criticized by others for its unhappy ending.

1881 He publishes Ghosts, which is about the undermining of moral idealism and which touches on the taboo subject of venereal disease; the London Daily Telegraph calls the play “a dirty act done publicly.”

1882 Ghosts is staged in Chicago, in Norwegian. In the play An Enemy of the People, which opens in Christiania, Ibsen tells the story of an idealistic truth-teller rejected by those around him; it also receives negative reviews.

1884 Ibsen publishes the poetic and symbolic drama The Wild Duck.

1885 Ibsen moves back to Munich, where he will spend the next six years.

1886 He completes Rosmersholm, which explores the conflict be tween unrestricted freedom and conservative traditions.

1890 He completes Hedda Gabler, about an idealistic but destructive woman; Oscar Wilde attends the opening and feels “pity and terror, as though the play had been Greek.” George Bernard Shaw praises Ibsen in a lecture, “The Quintessence of Ib senism” (published 1891).

1891 Ibsen returns to Norway and settles in Christiania. The Master Builder is published.

1893 The Master Builder premieres in Berlin; it is the first play in Ibsen’s final period, when symbolism features strongly in his dramas.

1894 Ibsen completes Little Eyolf, a play about parental responsibil ity. In London, Clement Scott establishes an anti-Ibsen league. Ibsen moves into an apartment on the corner of Arbiensgate and Drammensveien in Christiania, where he will reside until his death; there is now a museum on the site.

1896 Ibsen publishes John Gabriel Borkmann, a realistic drama about the explosive household of a wealthy man ruined by a prison term for embezzlement.

1899 The symbolic drama When We Dead Awaken is Ibsen’s last work to be published during his lifetime.

1900 Ibsen suffers his first stroke.

1901 After a second stroke, he will be bedridden until his death.

1906 Ibsen dies in Christiania on May 23.

INTRODUCTION

Ibsen’s reputation as Europe’s first and most consequential modern dramatist was made by scandal. The publication and performance of each new play unleashed storms of protest, mixing shock with aggression and disgust with censorship. Theater critics and audiences in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Ibsen’s native Norway denounced the latest provocation flowing from Ibsen’s pen with almost predictable frequency. These detractors found themselves attacked no less vehemently by a small but vocal band of defenders, such as George Bernard Shaw and William Archer in England and Georg Brandes in Scandinavia. Ibsen was a playwright capable of polarizing Europe into friends and enemies, forcing them to show their true colors; you were either for Ibsen or against him. As the debate about Ibsen escalated, this alternative turned into a more fundamental one: You were either for or against modern drama itself.

Many admirers of Ibsen later bemoaned the notoriety of their hero. The scandals, they claimed, focused on minor and accidental aspects of his work and therefore distracted from the poetic beauty of his plays and their imaginative treatment of the dramatic form. These calm and measured appreciations are justified enough, but they disregard one crucial fact—namely, that it was through these scandals that Ibsen came to be regarded not just as a well-known playwright, but also as the originator of modern drama. In order to be modern it is not enough to write compelling or even great plays; your plays must stir up the audience, strike them with surprise, attack their complacency. Being modern means offending the audience, so much so that the enraged audience can be seen as the primordial scene from which modern drama emerged. There is no author in the pantheon of modern drama whose name is not associated with provocation: Shaw and Wilde were censored; the openings of plays by Jarry and Artaud led to riots; and Brecht turned the provocation of the audience into a whole theory of modern drama. As much as connoisseurs of Ibsen want us to look beyond the provocation, this provocation is the first thing we must consider because it set the pattern on which the whole tradition of modern drama was modeled. Ibsen was the school for scandal from which all modern dramatists had to graduate.

Ibsen’s scandals, his claims to modernity, were primarily based on the content of his plays, the kinds of things they dared to depict and the names they dared to speak. The best fodder for outrage were, predictably enough, all things having to do with illicit sexual activities, most particularly the assorted sexually transmitted diseases, sometimes reminiscent of syphilis but at other times vague and not medically specific, that appeared in his most notorious plays, A Doll’s House and Ghosts. Other plays launched assaults on the bourgeois home and the nuclear family, depicted feminist rebellion against patriarchal society, and denounced the established Church. If these subjects made Ibsen enemies, they also made him friends—in particular, Shaw, whose polemical pamphlet The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891) celebrates Ibsen as rebel for leftist causes. What better place to unmask the lies of the nuclear family than through the bourgeois drawing-room drama, turned against itself? Ibsen openly professed various radical opinions outside his plays as well; at one point he wrote that the state should be abolished altogether. In Ibsen social radicalism and dramatic radicalism seemed to have come to a happy union.

A Doll's House

A Doll's House Peer Gynt and Brand

Peer Gynt and Brand The Master Builder and Other Plays

The Master Builder and Other Plays A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin)

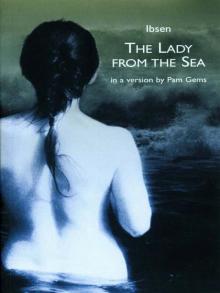

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) The Lady from the Sea

The Lady from the Sea