- Home

- Henrik Ibsen

The Master Builder and Other Plays Page 17

The Master Builder and Other Plays Read online

Page 17

ALLMERS [makes no reply. After a few moments he says]: No, I can’t take it in. I simply don’t see how it’s possible – this.

ASTA [laying a sympathetic hand on his arm]: My poor Alfred.

ALLMERS [staring at her]: Is it really true then, Asta? Or have I gone mad? Or am I just dreaming? Oh, if only it were a dream! Think how marvellous it would be if I were to wake up!

ASTA: Oh, how I wish I could wake you.

ALLMERS [gazing out across the water]: How pitiless the fjord looks today. Lying there so heavy and drowsy. Leaden grey – flecked with gold – and reflecting the rain clouds.

ASTA [beseechingly]: Oh, Alfred, don’t sit there staring at that fjord!

ALLMERS [not listening to her]: On the surface, yes. But down in the depths – there the fierce undertow runs –

ASTA [anxiously]: Oh, dear God in heaven – don’t think about those depths!

ALLMERS [regarding her tenderly]: You probably think he’s lying just out there, don’t you? But he isn’t, Asta. You mustn’t think that. You have to bear in mind, you see, how swiftly the current runs here. Straight out to sea.

ASTA [slumps over the table, sobbing, her hands over her face]: Oh, God – oh, God!

ALLMERS [sorrowfully]: Which is why little Eyolf is now so far – so very far away from the rest of us.

ASTA [looking up at him entreatingly]: Oh, Alfred, don’t say such a thing!

ALLMERS: Well, work it out for yourself. You who are so clever –. In twenty-eight – twenty-nine hours –. Let me see –! Let me see –!

ASTA [crying out and covering her ears]: Alfred –!

ALLMERS [pounding the table with his fist]: But can you see the point of such a thing, Asta?

ASTA [looking at him]: Of what?

ALLMERS: Of this thing that’s befallen Rita and me.

ASTA: The point of it?

ALLMERS [impatiently]: Yes, the point, I said. Because there has to be some point to it. Life, existence – this visitation of fate can’t be so totally pointless, surely.

ASTA: Oh, who can say anything for certain about these things, Alfred dear?

ALLMERS [with a bitter laugh]: No, no; you’re probably right. Maybe it is all quite random, Asta. Things just going their own way, like a wrecked ship, drifting rudderless. That could well be the case. – It almost seems that way, at least.

ASTA [thoughtfully]: What if it only seems so –?

ALLMERS [angrily]: Well? Can you unravel it for me perhaps? Because I can’t. [More gently] Here is Eyolf, all set to enter the life of the mind. Carrying within him such infinite possibilities. Rich possibilities, perhaps. Set to fill my life with joy and pride.1 And all it takes is for a demented old woman to come along – and show off a dog in a bag –

ASTA: But we don’t know how it actually came about.

ALLMERS: Oh, we know. Because the boys saw her rowing out across the fjord. They saw Eyolf standing alone out at the end of the jetty. Saw him gazing after her – and seem to swoon. [Voice trembling] And then he plunged in – and was gone.

ASTA: Yes, yes. But still –

ALLMERS: She has lured him into the depths. You can be sure of that.

ASTA: But, my dear, why should she do that?

ALLMERS: Ah – now – that’s just it! Why should she? There’s no retribution behind it. Nothing to atone for, I mean. Eyolf has never done her any harm. Never called her names. Never thrown stones at the dog. He had never even laid eyes on her or the dog until yesterday. So, no retribution. So groundless, all of it. So utterly pointless, Asta. – And yet the world order requires it.

ASTA: Have you spoken to Rita about all this?

ALLMERS [shaking his head]: I find it easier to talk to you about such things. [Heaving a sigh] And about everything else as well.

ASTA takes sewing things and a small paper package from her pocket. ALLMERS looks on absent-mindedly.

ALLMERS: What have you got there, Asta?

ASTA [picking up his hat]: Some black crape.2

ALLMERS: Oh, and what might that be for?

ASTA: Rita asked me to. May I?

ALLMERS: Oh, all right; fine by me.

She stitches the crape around the crown of his hat.

ALLMERS [sitting watching her]: Where is Rita?

ASTA: She’s wandering about up in the garden, I think. Mr Borgheim’s with her.

ALLMERS [rather surprised]: Really? Borgheim’s out here again today, is he?

ASTA: Yes. He came out on the midday train.

ALLMERS: That I hadn’t expected.

ASTA [sewing]: He was so very fond of Eyolf.

ALLMERS: Borgheim’s a faithful soul, Asta.

ASTA [with quiet warmth]: Yes, he is certainly faithful. That’s true.

ALLMERS [eyes fixed on her]: You really are fond of him.

ASTA: Yes, I am.

ALLMERS: But still you can’t bring yourself to –?

ASTA [cutting him off]: Oh, Alfred dear, don’t talk about that –!

ALLMERS: Yes, yes – just tell me why you can’t –?

ASTA: Oh no! I beg you, please. You really mustn’t ask me. Because it’s very embarrassing for me, you see. – There now. That’s your hat done.

ALLMERS: Thank you.

ASTA: And now for that left arm.

ALLMERS: Crape for that as well?

ASTA: Well, it is customary, you know.

ALLMERS: Oh, all right – do what you like.

She moves closer and proceeds to sew on the crape.

ASTA: Hold your arm still. So I don’t jab you.

ALLMERS [with a little smile]: This is just like old times.

ASTA: Yes it is, isn’t it?

ALLMERS: When you were a little girl you used to sit just like this, fixing my clothes.

ASTA: As well as I could, yes.

ALLMERS: The first thing you sewed on for me – that was black crape too.

ASTA: Oh?

ALLMERS: On my graduation cap. When Father died.

ASTA: Was I sewing as early as that? – Fancy, I don’t remember that.

ALLMERS: Well, no; you were just a little girl at the time.

ASTA: Yes, I was a little girl.

ALLMERS: And then two years later – when we lost your mother – you sewed a big crape armband for me too.

ASTA: I felt that was as it should be.

ALLMERS [patting her hand]: Yes, yes, and it was just as it should be, Asta. And then, when we were left all alone in the world, the two of us –. Are you finished already?

ASTA: Yes. [Gathering up her sewing things] Those were actually good times for us, though, Alfred. Just the two of us.

ALLMERS: Yes, they were. Hard though we toiled.

ASTA: You toiled.

ALLMERS [more brightly]: Oh, you toiled too, you know, in your own way – [smiling] you, my dear faithful – Eyolf.

ASTA: Ugh – don’t remind me of that silly nonsense with the name.

ALLMERS: Well, if you’d been a boy, you would’ve been called Eyolf.

ASTA: Yes, if, yes. But even after you had graduated –. [Smiling in spite of herself] To think that you could still be so childish.

ALLMERS: I was childish!

ASTA: Yes, looking back on it I really think you were. Because you were ashamed that you didn’t have any brothers. Only a sister.

ALLMERS: No, it was you, I tell you. You were ashamed.

ASTA: Oh yes, perhaps I was too, a bit. And I felt rather sorry for you –

ALLMERS: Yes, I suppose you did. And you looked out those old clothes I’d had as a boy –

ASTA: Those smart Sunday clothes, yes. Do you remember the blue blouse and the knickerbockers?

ALLMERS [giving her a lingering look]: How well I remember you putting them on and walking about in them.

ASTA: Yes, but I only did that when we were at home alone.

ALLMERS: And how earnest and how self-important we were, Asta. And me calling you Eyolf all the time.

ASTA: But A

lfred, you’ve never told Rita about this, have you?

ALLMERS: Yes, I think I did tell her about it once.

ASTA: Oh, but Alfred how could you!

ALLMERS: Ah, well you see – a man does tell his wife everything – or as good as.

ASTA: Yes, he would do, I suppose.

ALLMERS [as if coming to himself, puts his hand to his brow and leaps up]: Ah – how can I sit here and –

ASTA [standing up, giving him an anxious look]: What’s the matter with you?

ALLMERS: He was almost gone from me there. Completely gone he was.

ASTA: Eyolf!

ALLMERS: Here I was living in memories. And he wasn’t part of them.

ASTA: Oh, yes Alfred – little Eyolf was there behind it all.

ALLMERS: He wasn’t. He slipped out of my mind. Out of my thoughts. For a moment, while we were talking, I couldn’t see him before me. Completely forgot about him, all that time.

ASTA: Oh, but you must have some rest from your grief.

ALLMERS: No, no, no – that’s just what I must not do! That I may not do. Have no right to do. – And no heart to do, either. [Crossing to the right, in turmoil] I have only to linger out there, where he lies drifting down in the depths.

ASTA [going after him, holding on to him]: Alfred – Alfred! Don’t go down to the fjord!

ALLMERS: I have to go out to him! Let go of me, Asta! I need to get the boat.

ASTA [panic-stricken]: Don’t go down to the fjord, I say!

ALLMERS [giving in]: No, no – I won’t. Just leave me be.

ASTA [leading him back to the table]: You must give your mind a rest, Alfred. Come and sit down.

ALLMERS [goes to sit down on the bench]: Yes, all right – as you wish.

ASTA: No, don’t sit there.

ALLMERS: Yes, let me.

ASTA: No; don’t! Because then you’ll only sit and look out across the water –. [Pulling him down on to a chair so that he is facing left] There now. That’s better. [Sitting down on the bench] And now we can talk a little bit more.

ALLMERS [with an audible sigh]: It was good to ease the grief and the loss for a moment.

ASTA: You have to, Alfred.

ALLMERS: But don’t you think it’s awfully feeble and spineless of me – that I can?

ASTA: No, of course not. Because it must be impossible to concentrate on just one thing all the time.

ALLMERS: Well it’s impossible for me. Before you came down to find me I was sitting here tormented beyond words by this nagging, gnawing grief –

ASTA: Yes?

ALLMERS: And would you believe it, Asta –? Hm –

ASTA: What?

ALLMERS: In the midst of my torment I found myself wondering what we’d be having for dinner tonight.

ASTA [soothingly]: Yes, yes, well as long as there’s relief in it –

ALLMERS: Yes and do you know – I felt there was relief in it somehow. [Reaching a hand across the table to her] What a blessing it is that I have you, Asta. I’m so glad I do. Glad, glad – even in my grief.

ASTA [regarding him gravely]: Above all you should be glad that you have Rita.

ALLMERS: Well, that goes without saying, of course. But Rita is not my own kin. It’s not the same as having a sister.

ASTA [eagerly]: Really, Alfred?

ALLMERS: Yes, our family is one of a kind. [Half joking] Our names have always started with vowels.3 Remember how often we used to talk about that? And all our relatives – all of them equally poor. And all of us with the same eyes.

ASTA: You think I have them too –?

ALLMERS: No, you take after your mother completely, Asta. You don’t look at all like the rest of us. Not even Father. But even so –

ASTA: Even so –?

ALLMERS: Yes, I believe that even so our life together has stamped each of us with the other’s image. On our minds, I mean.

ASTA [deeply moved]: Oh, that you must never say, Alfred. It’s only me who’s taken your stamp. And it’s to you that I owe everything – everything that is good in the world.

ALLMERS [shaking his head]: You owe me nothing, Asta. On the contrary –

ASTA: I owe everything to you! You must be able to see that. No sacrifice has been too great for you.

ALLMERS [breaking in]: Oh, really – sacrifice! Don’t say such things. All I’ve ever done is love you, Asta. Ever since you were a baby. [After a brief pause] And besides, I always felt there were so many wrongs that I had to right.

ASTA [bewildered]: Wrongs! You?

ALLMERS: Not on my own account exactly. But –

ASTA [expectantly]: But –

ALLMERS: On Father’s.

ASTA [starting up from the bench]: On – Father’s! [Sitting down again] What do you mean by that, Alfred?

ALLMERS: Father was never very kind to you.

ASTA [sharply]: Oh, don’t say that!

ALLMERS: Yes, because it’s true. He didn’t love you. Not the way he should have.

ASTA [evasively]: No, perhaps not the way he loved you. But that’s understandable.

ALLMERS [persisting]: And he often treated your mother badly too. During those last few years, at any rate.

ASTA [softly]: But Mother was very, very much younger than him. Don’t forget that.

ALLMERS: Do you think they were ill-matched?

ASTA: They might have been.

ALLMERS: Yes, but even so –. Father, who was normally so gentle and warm-hearted –. So kind to everyone –

ASTA [quietly]: Mother may not always have behaved the way she should either.

ALLMERS: Your mother didn’t!

ASTA: Not always perhaps.

ALLMERS: Towards Father, you mean?

ASTA: Yes.

ALLMERS: I never noticed anything of that sort.

ASTA [standing up, fighting back the tears]: Oh, Alfred dear – let them rest – those who are gone.

She moves over to the right.

ALLMERS [rising]: Yes, let them rest. [Wringing his hands] But those who are gone – they don’t let us rest, Asta. Not by day or night.

ASTA [regarding him tenderly]: In time it will all become easier to bear, Alfred.

ALLMERS [eyeing her hopelessly]: Yes, don’t you think so too? – But how I’m to get through these terrible first days –. [Voice breaking] No, I don’t see how I can.

ASTA [imploring, placing her hands on his shoulders]: Go up to Rita. Oh please, I beg you –

ALLMERS [fiercely, pulling away]: No, no, no – don’t talk to me about that! Because I can’t, you see? [More calmly] Let me stay here with you.

ASTA: Yes, I won’t leave you.

ALLMERS [clutching her hand and holding it tight]: Thank you! [Looks out across the fjord for a moment] Where’s my little Eyolf now? [Smiling sadly at her] Can you tell me that – you, my big, wise Eyolf? [Shaking his head] No one in all the world can tell me that. I know only this one terrible thing: that I no longer have him.

ASTA [glancing up to the left and pulling her hand away]: They’re coming.

MRS ALLMERS and MR BORGHEIM come walking down the path through the wood; she in front; he following behind. She is sombrely dressed with a black veil over her head. He carries an umbrella under his arm.

ALLMERS [going to meet her]: How are you, Rita?

RITA [walking on past him]: Oh, don’t ask.

ALLMERS: What are you doing here?

RITA: Just looking for you. What are you doing?

ALLMERS: Nothing. Asta came down to me.

RITA: Yes, but before Asta came. You’ve been away from me all morning.

ALLMERS: I’ve been sitting here looking out across the water.

RITA: Ugh – how can you!

ALLMERS [shortly]: I’d prefer to be alone now!

RITA [pacing restlessly up and down]: And just sit still! On the one spot!

ALLMERS: I have absolutely nothing I need to be doing.

RITA: I can’t stand being anywhere. Least of all here – with the

fjord so near at hand.

ALLMERS: Yes exactly, the fjord is so close.

RITA [to BORGHEIM]: Don’t you think he should come back up with the rest of us?

BORGHEIM [to ALLMERS]: I think it would be better for you.

ALLMERS: No, no – just leave me where I am.

RITA: Then I’m staying with you, Alfred.

ALLMERS: Oh all right, do as you please. – You stay too, Asta.

ASTA [whispering to BORGHEIM]: Let’s leave them alone!

BORGHEIM [with a look of understanding]: Miss Allmers – shall we walk a little way – along the beach? For the very last time?

ASTA [picking up her umbrella]: Yes, come. Let’s walk a little way.

ASTA and BORGHEIM walk off together round the corner of the boathouse.

ALLMERS wanders up and down for a while. Then he sits down on a rock under the trees on the left in the foreground.

RITA [drawing closer to stand facing him with her clasped hands hanging in front of her]: Can you really grasp it, Alfred – the thought that we’ve lost Eyolf?

ALLMERS [gazing bleakly at his feet]: We’ll have to get used to that thought.

RITA: I can’t. I can’t. And then there’s that horrible sight, which will haunt me as long as I live.

ALLMERS [looking up]: What sight? What have you seen?

RITA: I didn’t see anything myself. Only heard about it. Oh –!

ALLMERS: You might as well just say it.

RITA: I took Mr Borgheim down to the jetty with me –

ALLMERS: What for?

RITA: To ask the boys how it happened.

ALLMERS: But we know how.

RITA: We found out more.

ALLMERS: Oh!

RITA: It’s not true that he was gone in an instant.

ALLMERS: Is that what they’re saying now?

RITA: Yes. They say they saw him lying on the bottom. Deep down in the clear water.

ALLMERS [grinding his teeth]: And they didn’t save him!

RITA: They probably couldn’t.

ALLMERS: They could swim, all of them. – Did they say how he was lying when they saw him?

RITA: Yes. They said he was on his back. And with big wide-open eyes.

ALLMERS: Wide-open eyes. But quite still?

RITA: Yes, quite still. And then something came and swept him out to sea. They called it an undertow.

ALLMERS [nodding slowly]: And that was the last they saw of him?

A Doll's House

A Doll's House Peer Gynt and Brand

Peer Gynt and Brand The Master Builder and Other Plays

The Master Builder and Other Plays A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin)

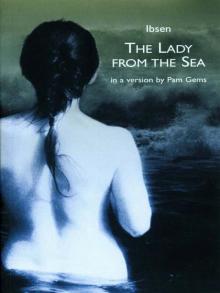

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) The Lady from the Sea

The Lady from the Sea