- Home

- Henrik Ibsen

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) Page 3

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) Read online

Page 3

The play’s proper title is a metaphor and, it becomes clear, a delusion. The pillars of society, and not least this society’s main pillar, Consul Bernick, are, by the end, shown to be less than solid, not least as ‘moral support’. The action takes place in Bernick’s house in ‘a moderately small Norwegian coastal town’, and it is from this place that the movement between ‘out there’ and ‘at home’ is activated. What sets the plot in this well-made and fairly conventional four-act play in motion is the return from ‘out there’, that is America, of Lona Hessel and her half-brother Johan Tønnesen. These two arrive back in a small community which is just on the verge of radical change, through the arrival of the railway. The consul’s behaviour in relation to his community, as well as an episode from his and Johan’s shared past, drive the plot on. Slowly, as much through action as through talk, the murky past and the morally dubious behaviour of Bernick are revealed, and his and his class’s questionable, paternalistic concern for their local community is exposed.

Ibsen’s satire in Pillars is fierce, and it may be interpreted as the exile’s perspective on his native Norway, the writer at this point having lived abroad, in Italy and Germany, for thirteen years. But it is also, and perhaps more interestingly, critical of simple oppositions between us and them. In the end, the world at home is not quite so ideal, nor the world out there perhaps quite so corrupt, as Rørlund would have us believe. The issue of provincialism, then, was being explored by Ibsen in his art; quite apart from being an important and perhaps inescapable feature of his own early reception abroad.

In the play Ibsen explores the function of lying and the costs of truth in bourgeois society, as well as showing how many may have reasons to long for a different social contract, one based on truth, freedom and equality. ‘And you call yourselves the pillars of the community’, a shocked Lona Hessel exclaims. But the play should not be reduced to a simple or symmetrical opposition of truth against lies; it is rather, as Inga-Stina Ewbank has suggested, a more ‘arabesque-like enquiry into why we say what we say’.17 In spite of the play’s conciliatory ending, with the consul’s response to the wonderfully ironic procession in his honour, it is hardly clear that he has passed the moral tests he has been exposed to through the plot’s various twists and turns. While there is a real leap between this and Ibsen’s next play in terms of its radicalism, we may nevertheless ask whether we should trust the reformist conclusion of this play or consider it ironic.18 Long before we get to this point, something more fundamental than an individual consul’s conversion has in any case been shown to be at stake, and it is worth noting that Bernick’s final declaration echoes Rørlund’s parodic speech in which he proclaims the coming of ‘a new age’, one of truth. It is far from clear how far Bernick’s transformation goes.19

The title’s term ‘samfund’ comes up in a great number of different contexts throughout the play, and is contested from the very beginning. ‘My community is not the consul’s community’, pronounces Aune, the shipwright, in the play’s first scene. Nor is this community, importantly, a community for women. Hilmar Tønnesen scoffs at the conservative Rørlund’s reading matter, Woman as Servant to the Community, and Lona Hessel not only articulates a demand for change, she embodies it by simply behaving as men’s equal. She does not understand the notions of ‘duty’ which are being imposed on her, and claims that she lives in a society in which women are invisible: ‘you don’t see women’. In a number of respects, Lona prefigures ‘The New Woman’, the controversial ideal of the educated, fiercely self-sufficient woman that emerged in the 1880s and ’90s. With her it is as if we are hearing a new voice, the voice of a woman speaking up for herself and rejecting the roles imposed upon her by society. That is a voice that famously comes into its own in Ibsen’s next play.

A Doll’s House

Ibsen’s earliest notes for Pillars of the Community indicate that he had planned to make the position of woman in a man’s world of business the central concern, even if other themes in the end became more prominent. In his working notes for his next play, he went further, observing that ‘a woman cannot be herself in today’s society’, since this was exclusively male.20 ‘There are two kinds of moral law, two kinds of conscience,’ he added, drawing on essentialist notions of the relationship between the genders, ‘one in man and a completely different one in woman’.21 Men not only wrote the laws, Ibsen remarked, but they acted as both prosecutors and judges.

In addition to these early ideas there is, more specifically, no doubt that Ibsen had been inspired by the example of the author Laura Petersen Kieler, an acquaintance whom he may be said to have mentored, even calling her his ‘skylark’.22 Hoping to help heal her husband’s tuberculosis, Kieler had secretly borrowed money in order to finance a trip to Italy and, while not in the end committing it, later entered into forgery when she struggled to repay the loan. Importantly, however, the similarities between Laura and Nora stop there. While Kieler’s husband had her locked up in a mental hospital and managed to gain custody over their children, before, two years later, letting her back into the family, Ibsen’s Nora has recourse to another solution: she rebels.

While not his greatest play in aesthetic terms, A Doll’s House is Ibsen’s greatest international achievement. Nora can, moreover, be counted among the most significant female characters in world drama, along with Antigone, Medea and Juliet.23 How can such an astounding and durable success be accounted for? The theatre historian Julie Holledge identifies three key factors which most often come up in response to this question. The first is aesthetic innovation, with the play being seen as introducing a new form of psychological realism in the theatre, not least in its representation of female characters. The second is Nora’s iconic status in women’s struggle for subjective freedom, and the third the special connection created between the audience and the play’s lead character. One of the reasons behind Ibsen’s phenomenal success in the theatre is no doubt related to his appeal within the profession, and particularly to actresses.

When he wrote to his Danish publisher three months before the play’s publication, Ibsen claimed that the play would ‘touch on problems, which must be called particularly topical’.24 The title Et Dukkehjem creates the impression that we, as readers and spectators, are invited to peer into a home where human beings, and women in particular, are, metaphorically, reduced to dolls. There is a contraction here of the larger social world we have witnessed in Pillars of the Community, and the action takes place over only a few days, showing Nora Helmer’s transformation from doll to independent woman.

A Doll’s House has no genre designation other than ‘A Play in Three Acts’, though Ibsen had referred to it as ‘the tragedy of contemporary life’ (‘nutids-tragedien’, literally ‘the tragedy of the now’) in his notes.25 The play was published in Copenhagen on 4 December 1879, and the first edition of 8,000 copies sold out almost immediately. A Doll’s House in fact had a relatively positive first reception in Norway, and Ibsen was almost universally praised for the play’s formal features, even if some queried its ideas. The reviews were followed, however, by a more heated debate on Nora’s choice, supposed immorality and on gender roles more generally.

So what does Nora in the end react or rebel against? Torvald Helmer is a lawyer who, when the play begins, has finally achieved financial security as director of the local bank. After years of illness and financial struggle, a new life seems to open up for his family of five. The first act gives us an irresponsible and rather lightheaded Nora, a product of a patronizing and protective husband and, before that, we later learn, a similarly minded father, who has treated her as his ‘doll child’. The power of naming, as well as the power to make laws and establish norms, the play suggests, is a male form of power. Torvald’s use of a variety of pet names for her, such as ‘squirrel’ and ‘song-lark’, is one of the ways in which the relationship is performed. In the first act it is already hinted that Nora has taken on responsibility, however, if in a misguided way, and

that there are other sides to her than those which she displays in her husband’s presence. When she understands that what she sees as her own brave action is not exempt from punishment by the legal system, she observes that this must be a ‘bad law’. The statement is on one level naive; on another level it is an indictment on how the law more generally regards women in her society. As the plot gradually unravels and the tension builds, Nora matures, so rapidly that it has always represented an artistic challenge to the actress playing the lead role.

The tarantella dance at the end of Act Two is a key scene, one which is equally characterized by authenticity and theatricality, in which the other and new Nora surfaces.26 She dances, her husband observes, ‘as if your life depended on it’, and when he later, in Act Three, considers her performance, he notes that there may have been something just a little ‘over-natural’ about it. At this stage Nora decides to throw off her ‘masquerade costume’ and utters the now famous words: ‘you and I have a lot to talk about’. The ensuing conversation not only demonstrates her quest for autonomy and freedom, and Torvald’s inadequate responses to her arguments and demands, it also shows how deeply connected her unhappy situation is with society’s regulation of the relationship between the sexes. I am ‘first and foremost a human being’ (often, in ideologically significant ways, mistranslated as ‘individual’ in English), Nora asserts, and her strong conviction that her womanhood, and the expectations invested in that womanhood, are secondary strengthens her resolve to make a radical choice: a break with both husband and – with necessity, due to her legal position – her children:

HELMER: Leave your home, your husband and your children! And you haven’t a thought for what people will say.

NORA: I can’t take that into consideration. I just know that it’ll be necessary for me.

HELMER: Oh, this is outrageous. You can abandon your most sacred duties, just like that?

NORA: What, then, do you count as my most sacred duties?

HELMER: And I really need to tell you that! Aren’t they the duties to your husband and your children?

NORA: I have other equally sacred duties.

HELMER: You do not. What duties could they be?

NORA: The duties to myself.

Nora’s existential choice seems to be forced upon her by society. But in adopting her husband’s and society’s language, so often used to contain and control women, she now speaks of her ‘duties’ towards herself, even ‘sacred’ ones. For some early Ibsen critics this meant that the play was ‘all self, self, self!’; for others, such as the feminists who gathered to watch the first proper London production of the play, it represented ‘either the end of the world or the beginning of a new world for women’.27

One of the recurring issues in the criticism of A Doll’s House is whether it is a play about the emancipation of women or about human freedom more generally. From a gender perspective, Toril Moi notes, the play’s key sentence is precisely Nora’s insistence that she is first and foremost a human being.28 In a radical refusal to stick to inherited notions of women’s role in family and society, Nora rejects the other identities available to her, both as ‘doll’ and as self-sacrificing ‘wife and mother’, and the play captures a historical transition of women moving from a status of ‘generic family member’ to becoming ‘individuals’.29 It is also, it may be added, a rejection of Torvald’s ‘pet names’ for her.

How can the fact of two people living together (the ‘samliv’ of the original) become a true marriage, Nora wonders. If A Doll’s House is nothing less than ‘a revolutionary reconsideration of the very meaning of love’, it is because it articulates new demands on the institution of marriage, as one between equals.30 And these demands originate in the situation of a particular individual, a woman. In spite of Ibsen’s early ideas about certain essential differences between man and woman, as expressed in his notes, the play itself effectively breaks with the notion of ‘separate spheres’.31 And it finds its dramatic material in the tension between ‘difference’ and ‘equality’. While at first seemingly basing his claim for equality on difference, in the end the play may seem to stress sameness. But it is not quite as simple as this, and Ibsen refused to give an answer. Does Nora want to be an ‘individual’ in Helmer’s sense? Her situation and longings can of course be generalized or shared by other human beings, but historically the performance of this play, it may be worth remembering, has ‘depend[ed] on a female body’.32 Sameness and difference continue to play themselves out as an unresolved paradox, and this tension is part of the continued attraction of A Doll’s House.

Variations on the key term ‘vidunderlig’ occur throughout A Doll’s House and are central to the play’s conclusion. In a fashion typical of Ibsen’s language, these central clusters of words expand and gather weight through being used in a number of different contexts, here, from the play’s beginning, with reference to material well-being and then to Nora’s romantic fictions.33 The term is close to ‘wonderful’, but stronger, and while ‘the miracle’ contains too powerfully religious connotations, this translation has opted for the somewhat weaker adjectival forms, such as ‘the miraculous’ and ‘the miraculous thing’. At the end of the play, something larger than a carefree material life or romantic love is shown to be at stake, something relating to a new, shared consciousness of mutuality.

The custom on the Victorian stage was to subject foreign drama, which was primarily imported from Paris, to thorough domestication. Characters, plots, cultural and moral codes were anglicized. Upon his arrival in the English-speaking world, Ibsen was initially exposed to the same treatment. In the soppy 1884 London adaptation of A Doll’s House, called Breaking a Butterfly, the Torvald Helmer figure (renamed Goddard) takes the blame for his wife’s forgery upon himself and forgives her (Flora or ‘Flossie’) in an intensely patronizing way. Towards the end of the play she proclaims that her husband has shown himself to be ‘a thousand times too good for me’, and in his last line, as he burns the compromising, forged note, Goddard can happily observe that ‘Nothing has happened, except that Flossie was a child yesterday: to-day she is a woman.’34 And no one leaves; the status quo is re-established.

It is difficult to get further away from the original, and it took five more years until the play was successfully performed in English, and in a more faithful version. This was the famous Novelty Theatre production, which premiered in London on 7 June 1889 and then went on a tour to Australia and New Zealand. The play’s theme and supposed message led to heated debate, but even the most conservative critics did not deny its effect on stage, or how it provided the leading actress, Janet Achurch, with a great role. The fact that a contemporary foreign playwright was treated with such respect, rather than being freely adapted and domesticated, was in itself striking. ‘Word for word Mr. Archer has faithfully translated the original play and not allowed one suggestion, however objectionable, to be glossed over,’ the conservative critic of the Daily Telegraph, Clement Scott, remarked.35 In a small way, this production also pointed towards more realistic staging and acting conventions in the Victorian theatre. The Novelty production made Ibsen’s name in Britain. On 1 July 1889 William Archer would note that ‘Ibsen has for the past month been the most famous man in the English literary world.’36

George Bernard Shaw, socialist and early ‘Ibsenite’, saw A Doll’s House as a radical turning point, and claimed that its crucial ‘new technical feature’ was ‘the discussion’.37 Until a certain point in the last act, Shaw noted in his polemical pamphlet The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891), A Doll’s House might, if a few lines were excised, be turned into a conventional French play with its secrets, devices such as the letter box and sudden turns in the plot. But at that crucial moment the heroine ‘stops her emotional acting and says: “We must sit down and discuss all this that has been happening between us.” ’ Here, Shaw claimed, this play founded ‘a new school of dramatic art’.38

Many contemporary critics found this move fundament

ally untheatrical, however, due to its lack of dramatic action, and later writers on the drama have also characterized Ibsen’s form as novelistic.39 It was not only a matter of a new and more complex psychology which broke with the old dramaturgy of stock characters and clear, easily recognizable gestures and emotions. Ibsen’s ‘retrospective technique’, in which many of the most significant events have taken place before the play begins, and are only gradually revealed, is even more prominent in the next play, Ghosts. This technique had its antecedents in Greek tragedy and Sophocles in particular, but what was new was Ibsen’s reactivation of it at a new juncture in history, at a different point in the development of the genre.

The final slamming of the street door remains one of the most famous endings in the history of Western theatre and it may, as much as Shaw’s favoured ‘discussion’, symbolically represent the beginning of modern drama. But this ending, including the expressed longing for the ‘miraculous thing’, is, importantly, one without definite closure. From the first publication of A Doll’s House the play has engendered alternative endings, sequels, prequels, adaptations, parodies and new artistic responses of all kinds, like few other plays in the canon. A Doll’s House has, more generally, proved itself astonishingly adaptable to new contexts; it still seems to contain stories that need to be told.

Ghosts

A Doll’s House was seen as a strong challenge to society’s gender and family norms. But it was his next play, which Ibsen finished during the autumn of 1881, which he ended up calling ‘A Family Drama’. After the reception of A Doll’s House, Ibsen, so often the master of reinvention, set himself a new task. Ghosts can be read as an exploration of what would have happened if Nora had chosen to stay, although the play should not, of course, be reduced to this. Mrs Alving is a woman who, we learn, left her husband after a year of marriage, but was subsequently persuaded to return. This episode and this choice come back to haunt her.

A Doll's House

A Doll's House Peer Gynt and Brand

Peer Gynt and Brand The Master Builder and Other Plays

The Master Builder and Other Plays A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin)

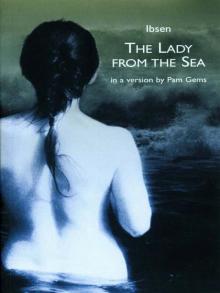

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) The Lady from the Sea

The Lady from the Sea