- Home

- Henrik Ibsen

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) Page 6

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) Read online

Page 6

However, for some words it is not the high frequency that counts. The only person using the word ‘bedærvet’ in A Doll’s House is Dr Rank, only twice, yet in Norwegian it is so stark and unpleasant as to stick out. The physician jokes to a slightly fatigued Mrs Linde that perhaps she is a tad ‘bedærvet’ on the inside – the word means rotten, rancid, gone off (indeed it is used in Enemy of the People to describe the putrefied waters at the Spa). Dr Rank has relatively few lines in the play, and this is almost the first thing he says. Yet only a few lines later Dr Rank repeats the word by describing Mr Krogstad as being ‘bedærvet’ to the very roots of his character. While previous translators have reflected the image of rottenness in relation to Krogstad, they have perhaps been too polite to parallel the unpleasantness in Dr Rank’s remark to Mrs Linde. However, it seems too noticeable a wording to ignore. Dr Rank’s use of the adjective is open to interpretation; it may simply mark his morbid humour induced by his own illness or his misanthropic tendencies or serve to foreshadow the relationship between Mrs Linde and Krogstad and the destruction they will bring to the Helmer household. Whatever the case, this verbal feature should be available to readers of Ibsen in English.

There is another arena for repeats in Norwegian that often automatically disappears in translation: the Norwegian predilection for creating compounds, where simpler words are combined to make a new concept. A noun like ‘stridslyst’ (directed at Dr Stockmann in Enemy of the People) might well be translated as belligerence, but it is actually made up of battle and wish and will therefore resonate with the two words ‘strid’ or ‘lyst’ elsewhere in the play. Similarly, Mr Billing uses ‘stridsmod’, which can mean determination or pluck, yet the word in Norwegian is made up from battle and courage. Such compounds and their simpler (often more graphic) components appear throughout the play, and to readers of the original they become part of a through-line of references to revolution, war, conflict and fighting at many points in the text. The linguistic options offered by composite words in Norwegian may be fortuitous in Ibsen’s writing, but never accidental. For the translator it is a particular challenge to keep this tightly woven textuality intact in English.

Finally, humour is always difficult to preserve in translation, but all the more important when we consider that Ibsen is mainly known as a serious, naturalistic dramatist. In particular, Pillars of the Community, in many respects a joyously theatrical play predating Ibsen’s more naturalistic works, moves with a rhythmic tempo largely sustained by comedic stage business.

Ibsen has a distinct tendency to poke fun at characters who think too highly of themselves, most often minor characters, including Aslaksen and Billing in Enemy of the People, and Rummel and Rørlund in Pillars of the Community. In the latter play Bernick’s egotistical view of the world is mostly expressed in unconscious little remarks, revealing his lack of self-awareness. Talking about his single sister, Bernick reassures Johan, who suspects she is rather unhappy, that she has plenty to keep her occupied: ‘hun har jo mig og Betty og Olaf og mig’ (literally meaning ‘after all, she has me and Betty and Olaf and me’), thus mentioning himself twice. Surprisingly, Ibsen’s carefully placed verbal slip has been ‘tidied up’ in previous translations.

We should also mention the difficulties of translating swear-words in Ibsen – a type of vulgarity that may also have a humorous effect – since these are impossible to reflect accurately, as indeed they generally are from language to language. The distribution of the related swear-words ‘fanden’ or ‘fan’/fa’n’ is telling in Ibsen’s plays. Both have their origin in the word for devil, and both words turn up in other plays, generally serving as a marker of class. The former, longer version is tolerable for a man of the middle class if used in a moment of exasperation and is used liberally by Dr Stockmann and Mr Billing. The shorter pronunciation is far more vulgar and is generally used by working-class characters, and at a lower threshold of emotion. Those who use it in these plays are the carpenter Mr Engstrand in Ghosts, the old tanner Morten Kiil in An Enemy of the People and a couple of people in the crowd scene in Enemy of the People, one of whom shouts ‘fy for fan”. This, even to a modern Norwegian, is as offensive as the f-word in today’s English.

Although these four plays are translated with the reader in mind, we have sought to reflect the spirit and playability of Ibsen’s dialogue. For a long time there has been a tendency, particularly in the social dramas featured in this volume, to focus wholly on the moment-by-moment believability of the dialogue. Yet Ibsen’s genius lies in his capacity to create an intricate dramatic tapestry that works on multiple levels, simultaneously naturalistic and highly theatrical. Ultimately it is this craftsmanship that we hope we have captured. Most importantly, we hope that these translations offer the Anglophone reader without direct access to the original the possibility of interrogating and interpreting these texts anew.

Of course, however hard a translator aims at objectivity, translation is always a matter of interpretation, and true ‘meaning’ a source of endless debate. Ultimately our translations can only contribute to the on-going discussion about Ibsen’s work. We have to thank our editorial team for setting the exciting parameters within which we have worked, and our expert readers, who have often presented us with alternative and insightful readings and who have contributed so generously and patiently to our journey of investigation.

Deborah Dawkin

Erik Skuggevik

A Note on the Text

This Penguin edition is the first English-language edition based on the new historical-critical edition of Henrik Ibsen’s work, Henrik Ibsens Skrifter (2005–10) (HIS). The digital edition (HISe) is available at http://www.ibsen.uio.no/forside.xhtml. The texts of HIS are based on Ibsen’s first editions.

PILLARS OF THE COMMUNITY1

* * *

Characters

CONSUL2 KARSTEN BERNICK

MRS3 BETTY BERNICK, his wife

OLAF, their son, thirteen years old

MISS MARTA BERNICK, the consul’s sister

JOHAN TØNNESEN, Mrs Bernick’s younger brother

MISS LONA HESSEL, Mrs Bernick’s older step-sister

MR HILMAR TØNNESEN, Mrs Bernick’s cousin

MR RØRLUND, a schoolmaster 4

MR RUMMEL, a merchant5

MR VIGELAND, a tradesman

MR SANDSTAD, a tradesman

DINA DORF, a young girl living in the Bernicks’ house

MR KRAP, the consul’s chief clerk

MR AUNE, shipwright at Bernick’s yard

MRS RUMMEL, wife of Mr Rummel

MRS HOLT, wife of the postmaster

MRS LYNGE, wife of the doctor

MISS RUMMEL

MISS HOLT

THE TOWN’S CITIZENS AND OTHER INHABITANTS, FOREIGN SAILORS, STEAMSHIP PASSENGERS, ETC.

The action takes place in Consul Bernick’s house in a moderately small Norwegian coastal town.

Act One

A spacious garden room in Consul Bernick’s house. In the foreground to the left a door leads into the consul’s room; further back on the same wall is a similar door. In the middle of the opposite wall is a large entrance door. The wall in the background consists almost completely of plate glass with a door opening out on to wide garden steps, over which hangs a sunshade. Below the steps, part of the garden can be seen, enclosed by a fence with a small gate. Beyond this and running along the fence is a street, lined on the opposite side with small wooden houses painted in light colours. It is summer, and the sun is shining warmly. Now and then people walk past in the street, some stopping to talk, some doing their shopping at a little shop on the corner, etc.

A group of ladies is seated round a table in the garden room. At the centre of the table sits MRS BERNICK. To her left sits MRS HOLT with her daughter, followed by MRS RUMMEL and MISS RUMMEL. To the right of MRS BERNICK sit MRS LYNGE, MISS BERNICK and DINA DORF. All the ladies are busy sewing. On the table lie big piles of half-finished and cut-out linen garments and othe

r articles of clothing. Further back, at a small table, on which there are two potted plants and a glass of squash, sits the schoolmaster, MR RØRLUND, reading aloud from a book with gilt edges, although only the occasional word is audible to the audience. Outside in the garden OLAF BERNICK runs about, shooting at things with a bow and arrow.

A short while later MR AUNE comes quietly in through the door on the right. The reading is temporarily interrupted; MRS BERNICK nods to him and points towards the door on the left. AUNE goes quietly over and knocks gently twice on the consul’s door, pausing between each knock. KRAP, the CONSUL’s chief clerk, carrying his hat in his hand and papers under his arm, comes out of the room.

KRAP: Oh, it’s you knocking?

AUNE: The consul sent for me.

KRAP: He did indeed; but can’t see you; he’s delegated it to me to –

AUNE: To you? I’d have preferred –

KRAP: – delegated it to me to tell you this. You have to put a stop to these Saturday lectures for the workers.

AUNE: Oh? But I thought I could use my free time –

KRAP: You can’t go using your free time to make the men useless in their work time. Last Saturday you were speaking on the harm that would come to the workers from our new machinery and the new working methods in the shipyard. Why are you doing this?

AUNE: I do it to uphold6 the community.

KRAP: Extraordinary! The consul says it destabilizes the community.

AUNE: My community is not the consul’s community, Mr7 Chief Clerk! As foreman of the Workers’ Association8 I have to –

KRAP: You are first and foremost foreman of Consul Bernick’s shipyard. You have first and foremost a duty towards the community which is Consul Bernick’s company; because it’s what we all live by. – So, now you know what the consul had to say to you.

AUNE: The consul wouldn’t have said it in that way, Mr Chief Clerk, sir! But I know who I have to thank for this. It’s that damned American ship that’s in for repairs. Those people want the job done in the way they’re accustomed to over there, and that’s –

KRAP: Yes, yes, yes; I can’t get involved in long-winded discussions. You know the consul’s opinion now, and that’s that! Could you go back down to the yard; that might be useful; I’ll come down myself in a bit. – Excuse me, ladies.

He nods and exits through the garden and down the street. MR AUNE walks quietly out to the right. The SCHOOLMASTER, who during the preceding hushed conversation has continued reading aloud, finishes the book soon afterwards and snaps it closed.

MR RØRLUND: And that, my dear lady listeners, brings us to the end.

MRS RUMMEL: Oh, what an instructive tale!

MRS HOLT: And so moral!

MRS BERNICK: Such a book gives us a great deal to think about.

MR RØRLUND: Oh yes; it forms a salutary contrast to what we unfortunately see in the newspapers and magazines every day. The gilded and rouged exterior that these larger societies and communities9 present us with – what does it actually conceal? Hollowness and decay, if you ask me. No moral bedrock under their feet. In a word – they are whited sepulchres,10 these great modern-day societies.

MRS HOLT: Yes, how terribly true.

MRS RUMMEL: We need only look at the American crew docked here right now.

MR RØRLUND: Yes well, such dregs of humanity I’d really rather not discuss. But even in more elevated circles – how are things there? Doubt and fermenting disquiet on every side; discord and uncertainty in everything. Just look at how family life is undermined out there. Look how the voice of wanton revolt shouts down the most solemn of truths.

DINA [without looking up]: But aren’t lots of great things being done out there too?

MR RØRLUND: Great things –? I don’t understand –

MRS HOLT [amazed]: Good heavens, Dina –!

MRS RUMMEL [at the same time]: Really, Dina, how could you –?

MR RØRLUND: I don’t think it would be healthy if such things were to gain entry here. No, we should thank our Lord that things are as they are, here at home. Admittedly tares grow in amongst the wheat here too,11 unfortunately; but then we strive to weed them out as best we can. We must keep our community pure, dear ladies – keep out all the untested things that an impatient age wishes to force upon us.

MRS HOLT: And there are more than enough of those, unfortunately.

MRS RUMMEL: Yes, it was by a hair’s breadth we didn’t end up with a railway into town last year.

MRS BERNICK: Well, Karsten put a stop to that.

MR RØRLUND: Providence, Mrs Bernick. You can be sure your husband was an instrument in the hand of one higher when he refused to take on that scheme.

MRS BERNICK: And yet he had to read so many malicious things in the papers. But we’re completely forgetting to thank you, Mr Rørlund. It really is more than kind of you to sacrifice so much time to us.

MR RØRLUND: Not at all; now with the school holidays –

MRS BERNICK: Yes, yes, but it’s a sacrifice nonetheless, Mr Rørlund.

MR RØRLUND [moves his chair in closer]: Don’t mention it, my good lady. Aren’t you all making a sacrifice for a good cause? And making it willingly and gladly, too? These morally corrupted individuals for whose betterment we work are like wounded soldiers on a battlefield. You, my dear ladies, are the Volunteer Nurses,12 kind-hearted sisters plucking the lint for these unhappy injured souls, tenderly dressing their wounds, mending and healing them –

MRS BERNICK: What a heavenly gift it must be to be able to see everything in such a beautiful light.

MR RØRLUND: As regards that, a great deal is inborn; although a great deal can also be developed. It’s simply a matter of seeing things in the light of a solemn vocation. Yes, what do you say, Miss Bernick? Don’t you find that you’ve somehow found a firmer foundation to stand on since you offered yourself up to your school work?

MISS BERNICK: Oh, I’m not sure what to say. When I’m down there in the schoolroom, I often wish I was far out on the wild sea.

MR RØRLUND: Well, these are the things we wrestle with, my dear Miss Bernick. But we must close the door against such restless guests. The wild sea – well naturally you don’t mean that literally; you mean the vast swell of human society where so many run aground. And do you really put so much value on the life that you hear buzzing and bubbling away outside? Just look down into the street. Out there people are going about in the hot sun, sweating and fretting over their petty concerns. No, those of us sitting here in the cool, our backs turned to the source of this disturbance, are most definitely better off.

MISS BERNICK: Yes, you’re right, I’m sure –

MR RØRLUND: And in a house like this – in a good, pure home, where family life reveals itself in its most beautiful form – where peace and harmony preside – [To MRS BERNICK] What are you listening to, Mrs Bernick?

MRS BERNICK [turned towards the door furthest forward to the left]: They’re getting rather loud in there.

MR RØRLUND: Is something in particular going on?

MRS BERNICK: I don’t know. I can hear somebody’s in there with my husband.

HILMAR TØNNESEN, with a cigar in his mouth, enters the door from the right, but pauses at the sight of the large group of ladies.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Oh, I do apologize – [Wants to withdraw.]

MRS BERNICK: No, Hilmar, do come in, you’re not disturbing us. Did you want something?

HILMAR TØNNESEN: No, I just wanted to look in. – Good morning, ladies. [To MRS BERNICK] So, what’s the outcome?

MRS BERNICK: Of what?

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Bernick’s drummed up this meeting.

MRS BERNICK: Oh? About what exactly?

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Oh, it’s this railway nonsense again.

MRS RUMMEL: No, is that possible?

MRS BERNICK: Poor Karsten, is he to have still more unpleasantness –

MR RØRLUND: But what should we make of this, Mr Tønnesen? Consul Bernick made it absolutely clear

last year that he didn’t want any railway.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Yes, I thought that too, but I met Chief Clerk Krap, and he told me that this railway business13 was back on the agenda, and that Bernick was holding a meeting with three of the town’s investors.

MRS RUMMEL: Yes, that’s what I thought – that I heard Rummel’s voice.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Oh yes, Mr Rummel’s in on it naturally, and then there’s Mr Sandstad from up the hill, and Mikkel Vigeland – ‘Holy Mikkel’ as they call him.

MR RØRLUND: Hrrm –

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Apologies, Mr Rørlund.

MRS BERNICK: And it was so nice and peaceful here just now.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: Well, I, for my part, wouldn’t object to them starting to quarrel again. It would be a diversion at least.

MR RØRLUND: Oh, I think we could do without that kind of diversion.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: That’s all according to one’s constitution. Certain natures require the occasional harrowing battle. But sadly that’s not something provincial life offers much of, and it isn’t given to everyone to – [Leafs through the SCHOOLMASTER’s book] ‘Woman as Servant to the Community’.14 What sort of bunkum is this?

MRS BERNICK: Goodness, Hilmar, you oughtn’t say that. You’ve obviously not read the book.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: No, and nor do I intend to read it.

MRS BERNICK: You’re not quite yourself today, it seems.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: No, I am not.

MRS BERNICK: Didn’t you sleep well last night, perhaps?

HILMAR TØNNESEN: No, I slept very badly. I took a stroll yesterday evening on account of my illness. Drifted up to the club and read a travelogue from the North Pole. It has a certain galvanizing effect, following people in their battles with the elements.

MRS RUMMEL: But it doesn’t seem to have agreed with you too well, Mr Tønnesen.

HILMAR TØNNESEN: No, it agreed with me extremely badly; I lay the entire night tossing and turning in a half sleep, dreaming I was being pursued by some ghastly walrus.

A Doll's House

A Doll's House Peer Gynt and Brand

Peer Gynt and Brand The Master Builder and Other Plays

The Master Builder and Other Plays A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin)

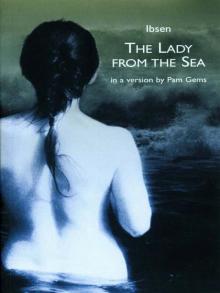

A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin) The Lady from the Sea

The Lady from the Sea